Throughout the life of Rome, from its humble beginnings as a small town into a behemoth of a military superpower, a variety of factors played key roles in its sustainability. While much of the anicent world has been lost to time, we can still find artifacts today that point to significant events of the past. Three artifacts that represent the great legacy of ancient Rome include the Twelve Tables for revolutionizing Roman law; the Tusculum portrait, which depicts Julius Caesar, who turned the Republic into the Empire; and the famous Colosseum for its architectural prowess and representation of life and entertainment.

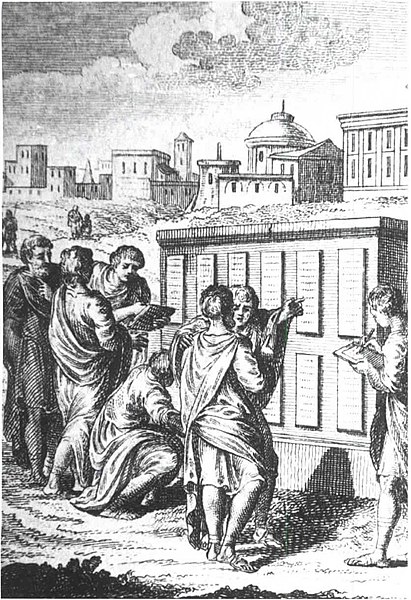

Decades into the Roman Republic, in the middle of the fifth century BCE, ten men were assigned the task of composing a list of laws for both the upper (patrician) class, and the lower (plebian) social class to abide by. After refining the subsequently written laws, they were inscribed on bronze tablets and consolidated into a stone structure called the Twelve Tables.(1) This artifact not only serves as the earliest attempt at creating a code of law, but also remains as the oldest piece of writing recorded from the ancient Roman civilization. The Twelve Tables outline laws that defined Roman life at the time, and onwards into the empire, containing sections explaining court procedure, debt, family, inheritance, possession and property, torts, public law, sacred law and any relevant supplementary law.(2)

Roman citizens examining the Twelve Tables

While the laws are fairly archaic (as must be expected for ancient society), they demonstrate the independence of Rome at this point in its history, and draws heavily off of influences such as the Code of Hammurabi of Code of Ur-Nammu. Ancient sentiments like the “eye for an eye” retaliation principle remain, and most punishments involve gruesome execution. Regardless, the Twelve Tables show how a society like Rome can grow and develop civilized and codified expectations of citizens, and how this was required for the civilization to grow to a massive world superpower. It’s also worth noting that the laws are largely secular, illustrating the laws of many future successful societies, attempting to separate potentially controversial and subjective religious politics from a more defined and objective system of right and wrong.(3) The original Twelve Tables were destroyed when Rome was sacked by Gaul around 390 BCE, but the laws have been mentioned and repeated throughout history, and a replica currently exists in the Museum of Roman Civilization.

Current replication of the Twelve Tables, located in the Museum of Roman Civilization

The Roman Republic, fortified by codified laws, existed for centuries. In 100 BCE, (potentially the most) famous Roman figure, Julius Caesar, was born. By 59 BCE, Caesar formed a political alliance with general Crassus and Roman leader, Pompey the Great. This alliance, known as the First Triumvirate, quickly fell after Caesar utilized his tactical skills to conquer Gaul. With these resources, Caesar built up his military up to such a strength that his allies were jealous.(4) As a result, a civil war was waged between Caesar and Pompey. Pompey had the strength of the Senate and their army, but Caesar won the battle using his impressive force.(5) Caesar took on a position of dictatorship over Rome, and led them through political negotiations with other enemies and allies before the Senate plotted to kill him in 44 BCE, as was illustrated in Shakespeare’s recounting of his life. Off of Julius, his nephew and adopted son, Octavian (who later took on his name as a title to become Caesar Augustus) became the first emperor of the Roman Empire.(6) Julius Caesar’s shift in the political structure of Rome caused years of military domination under a variety of competent and incompetent leaders, removing many of the complications that came with electing leaders in the republic. While most relics that portray the rule or power of leaders have been destroyed, there’s one known statue of Julius Caesar that was built in his lifetime: the Tusculum portrait. Dated to the latter years of Caesar’s rule, the bust includes similar features to those of coins illustrating him at the time.(7) After being found by Lucien Bonaparte, the statue was displayed in the Louvre, before being replicated and kept in a variety of private collections.(8) This portrait represents the political power and influence of Julius Caesar, as well as the distinctive, realistic artstyle of the Romans at the time of its conception. All in all, the Tusculum portrait is a snapshot of how rulers were heralded among Roman citizens, and the pivotal changes that Caesar brought to the civilization.

The Tusculum Portrait

Following the transformation from a republic into an empire, Roman life improved as the empire dominated during the beginning of the Common Era. With a strong military and expendable resources, the civilization could place more emphasis on its cultural aspects, such as art, architecture, and sport. In 72 CE, Emperor Vespasian established plans to build a large arena initially named the Flavian Amphitheatre. The building was finished in 80 CE by his son, Titus. The arena has stood the test of time, with its 80 arched entrances and 45 metre tall exterior still existing (albeit partially damaged), over twenty centuries down the line.(9) The Colosseum’s original intent was to host gladiator battles, where bodies would fall on the blood red sand through the means of swords, lances, and tridents. Gladiator fights weren’t the only contests, as other spectator events focused on hunting dangerous animals (like wild cats, bears or bulls) or killing defenseless animals (deer, ostriches, etc.) occurred daily. This intense violence and bloodshed would be mostly done away with in 404 CE after the rise of Christianity changed the morals of Roman citizens.(10) Beyond the depiction of change in daily life and entertainment for the Romans, the Colosseum is also a monument to the legacy of Roman architecture. Similarities to Greek architecture are present in beam-topped columns that the structure is composed of, but the arches included are distinctly Roman.(11)

The Roman Colosseum

The Roman architectural design philosophy is further exhibited in the Arch of Constantine, located nearby the Colosseum and built in 312 CE to commemorate Constantine the Great taking over the Western Roman Empire. Quite obviously containing arches, given its namesake, the structure portrays Roman art in the reliefs displayed on its side and foreshadows the power of Constantine: specifically, the changes he brought through the decriminalization of Christianity.(12) In the structural makeup of the Colosseum and the Arch of Constantine, we see more of Rome’s legacy form. This outlines the fortification of Rome’s culture through its strength and success.

The three artifacts of the Twelve Tables, the Tusculum portrait and the Colosseum, though deteriorated over time, represent critical developments in the history of Rome. Showing key aspects of law and social class, politics and art, and architecture and daily life, respectively, the archaeological discoveries made over the years following the decline of the ancient Roman civilization point to how an ancient society flourished in its time. With this knowledge, we can look back on the past and plot for the future through the direction we came from and the direction we must go.

Footnotes

(1) Kreis, Steven. “The Laws of the Twelve Tables, c.450 B.C.” The History Guide. Last modified 2001. http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/12tables.html.

(2) Adams, John P. “The Twelve Tables.” California State University, Northridge. Last modified June 10, 2009. https://www.csun.edu/~hcfll004/12tables.html.

(3) Cartwright, Mark. “Twelve Tables.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 11, 2016. https://www.ancient.eu/Twelve_Tables/.

(4) Biography. “Julius Caesar.” Biography.com. Accessed April 19, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/julius-caesar-9192504.

(5) Advameg, Inc. “Julius Caesar Biography.” Notable Biographies. Last modified 2018. http://www.notablebiographies.com/Br-Ca/Caesar-Julius.html.

(6) Grant, Michael. “Augustus.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last modified April 13, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Augustus-Roman-emperor.

(7) Slawth Staff. “The Tusculum Portrait.” Slawth. Last modified August 12, 2017. https://www.slawth.com/2017/08/12/the-tusculum-portrait/.

(8) Wikipedia contributors, “Tusculum portrait,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tusculum_portrait&oldid=825546471

(9) Rome.info. “Roman Colosseum.” Rome.info. Last modified 2003. https://www.rome.info/colosseum/.

(10) Cartwright, Mark. “Colosseum.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified November 6, 2012. https://www.ancient.eu/Colosseum/.

(11) Hopkins, Keith. “The Colosseum: Emblem of Rome.” BBC. Last modified March 22, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/colosseum_01.shtml.

(12) Findley, Andrew. “Arch of Constantine.” Khan Academy. Last modified November 25, 2105. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/late-empire/a/arch-of-constantine.

Bibliography

Adams, John P. “The Twelve Tables.” California State University, Northridge. Last modified June 10, 2009. https://www.csun.edu/~hcfll004/12tables.html.

Advameg, Inc. “Julius Caesar Biography.” Notable Biographies. Last modified 2018. http://www.notablebiographies.com/Br-Ca/Caesar-Julius.html.

Biography. “Julius Caesar.” Biography.com. Accessed April 19, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/julius-caesar-9192504.

Cartwright, Mark. “Colosseum.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified November 6, 2012. https://www.ancient.eu/Colosseum/.

Cartwright, Mark. “Twelve Tables.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 11, 2016. https://www.ancient.eu/Twelve_Tables/.

Findley, Andrew. “Arch of Constantine.” Khan Academy. Last modified November 25, 2105. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/late-empire/a/arch-of-constantine.

Grant, Michael. “Augustus.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last modified April 13, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Augustus-Roman-emperor.

Hopkins, Keith. “The Colosseum: Emblem of Rome.” BBC. Last modified March 22, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/colosseum_01.shtml.

Kreis, Steven. “The Laws of the Twelve Tables, c.450 B.C.” The History Guide. Last modified 2001. http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/12tables.html.

Layers of Rome UTEP. “Arch of Constantine with Dr. Ronald Weber (NEH).” YouTube. April 16, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPz7NY2ruf4.

“MrJennings”. “Twelve Tables: All.” flickr. 2005. https://www.flickr.com/photos/mrjennings/62005017/in/album-1352195/.

Poupeau, Gautier. “Exposition au Grand Palais “Moi, Auguste, empereur de Rome”.” Wiki Commons. 2014. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:C%C3%A9sar_(13667960455).jpg.

Rome.info. “Roman Colosseum.” Rome.info. Last modified 2003. https://www.rome.info/colosseum/.

Slawth Staff. “The Tusculum Portrait.” Slawth. Last modified August 12, 2017. https://www.slawth.com/2017/08/12/the-tusculum-portrait/.

“trialsanderrors”. “The Colosseum, Rome, Italy.” Wiki Commons. 1986. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_%E2%80%A6trialsanderrors_-_The_Colosseum,_Rome,_Italy,_ca._1896.jpg.

“Twelve Tables Engraving.” Wiki Commons. 2014. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Twelve_Tables_Engraving.jpg.

Wikipedia contributors, “Tusculum portrait,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tusculum_portrait&oldid=825546471